Natalie Mitchell, a first-year MA Contemporary Literature & Culture student, shares insights from Professor Marina Warner’s lecture that took place as part of the celebration of the 100-year anniversary of Birkbeck joining the University of London.

Professor Dame Marina Warner took her audience on a fascinating journey through the role of mapping in storytelling and memory, in her lecture, which forms part of the 100 Years of the University of London lecture series. Using Alfred Korzybski famous axiom ‘the map is not the territory’, which suggests that a map cannot encompass the true quality of a place, Professor Warner considered the re-imagining of place and how mapping can become a rebellious act.

She began the lecture considering the many roles of cartography in territory making, defining borders, resources, military and governance, and how this informs our memory of place. The map attempts to ‘actualise history’ through naming, marking and dividing, but the construction of history is a type of narrative. A point Professor Warner emphasised through the words history and story, which are the same in many languages. As such, mapping can control the narrative of a place and becomes an important tool for colonisers, although it may bear little resemblance to the reality of a place by its indigenous people.

The activity of creating maps can also realise fiction, such as the detailed fictional maps in the novels Gulliver’s Travels and The Lord of the Rings. Similarly, star maps give mythical gods a presence in reality through the stargazer’s eye and theme parks and Disney castles parody real locations through the child’s imagination. In this way, the fictional locations of stories can become real locations; these narratives ‘folding back’ onto the actual.

Professor Warner went on to suggest that the map can function in time as well as space, making the past present. This was particularly notable in Emma Willard’s mapping of aboriginal tribes in America and her Progress of the Roman Empire, charting time using the course of the Amazon river. These reworkings of maps can also perform a ‘historical resistance’ as seen in Layla Curtis’ NewcastleGateshead collaged map of all the places renamed after those cities, which highlights the colonial activity of claiming places through naming. Such use of cartography revealed the potential rebellious nature the renaming of maps can perform.

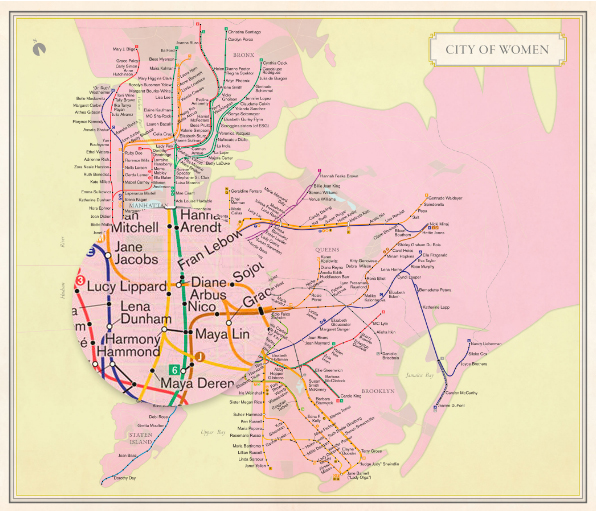

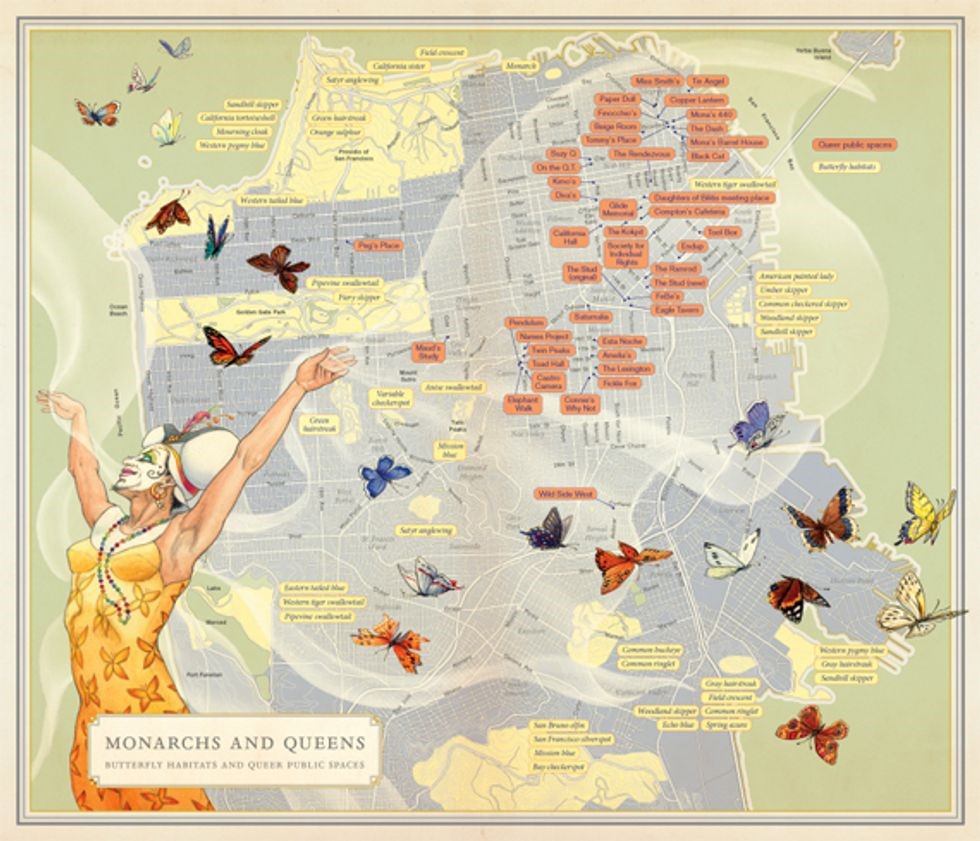

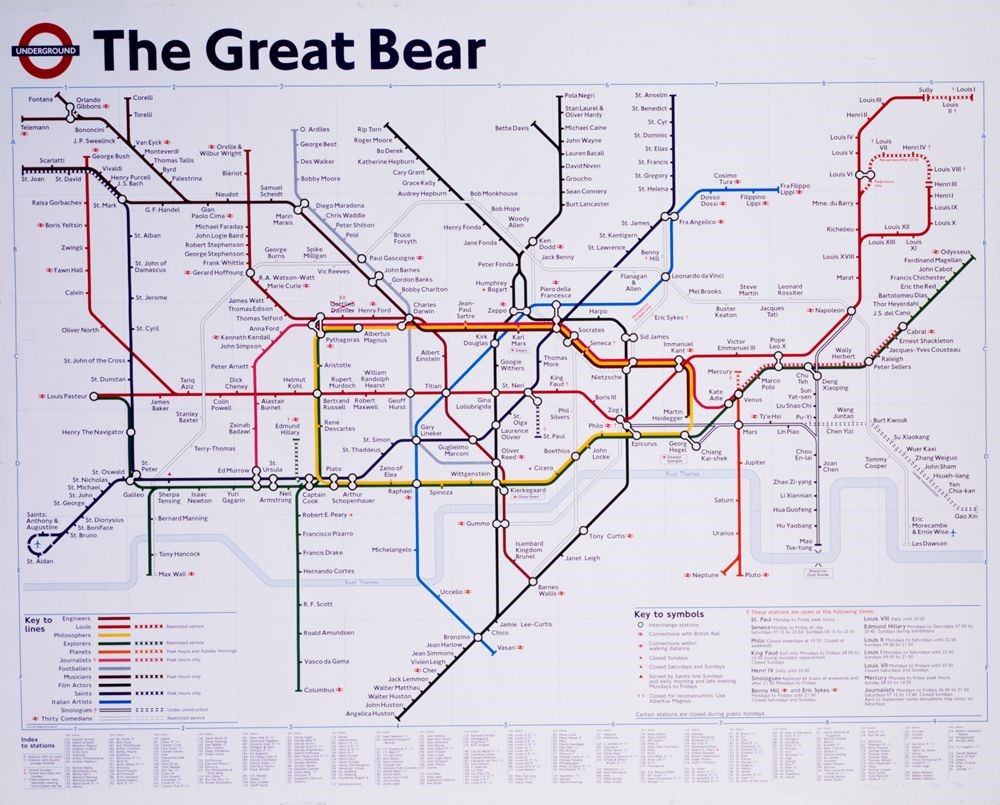

This type of resistance was expanded further by Professor Warner through many recent examples of the renaming and reworking of maps and places. In Paris in 2015, Osez le Feminisme flyered the city’s street signs, renaming them to notable women from history. Artists have also reimagined places via the redrawing of maps, such as Rebecca Solnit’s and Adam Dant’s maps, which create a visual narrative, questioning the authority of the map and returning to a cartography blending art and science. Similarly, Simon Patterson’s iconic reworking of the London tube map in his work The Great Bear renamed the stations after a myriad of famous and forgotten figures from history. Through each of her examples, Professor Warner showed how the reimagining of the map ‘makes the familiar unfamiliar’ and how a sense of place can be reclaimed by those in situ.

Professor Warner’s lecture was bookended by her recent work with a collective of young migrants in Palermo, Sicily, through the Stories in Transit workshop project Giocherenda. These workshops involved the young people developing stories of the city using the figure of The Genius of Palermo, a 15th century icon who has become a synonymous symbol of the city. The workshop took place around the city, where the young people placed the historical figure in different locations. Through this, they could develop their own sense of their new home in Palermo, but through the use of the city’s history. She expressed how it was the children who wanted to use mapping in their story creations and in doing so created a sense of belonging in an unfamiliar place.

Professor Warner concluded her lecture by emphasising the importance of continuing to create stories. Storytelling is an action and a way of history-making and in the days of fake news and big data, it is even more paramount.

Further information:

- Birkbeck’s 100 years of University of London celebration

- The Department of English Theatre and Creative Writing