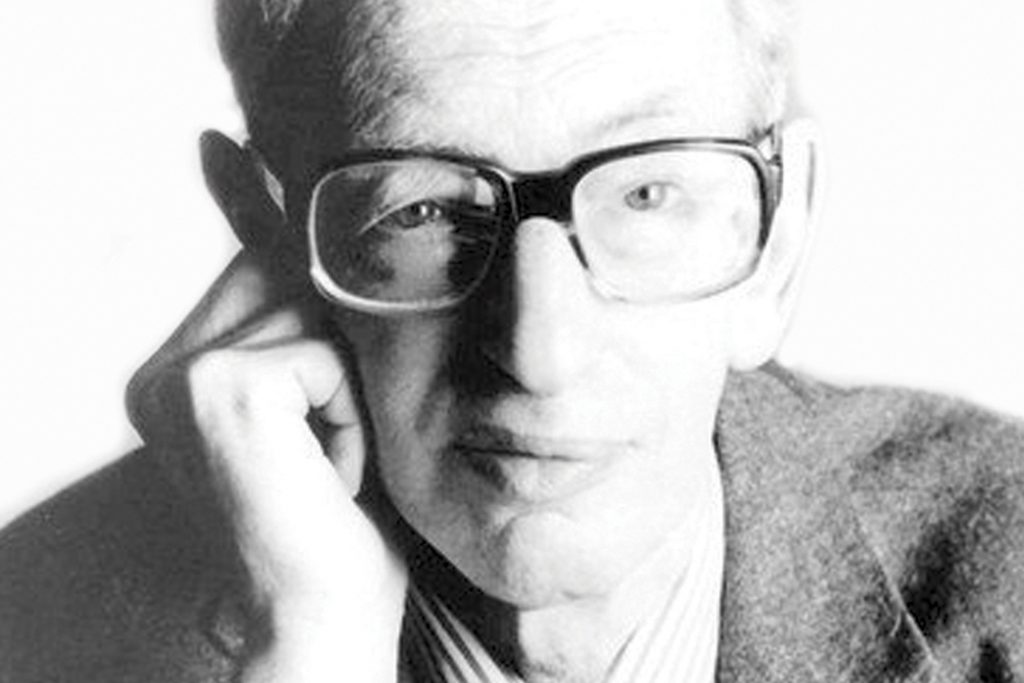

Martin Birch, untitled drawing (Mr A moves in mysterious ways). Credit: Adamson Collection / Wellcome Trust.

The Adamson Collection is, in every sense, a remarkable archive, encompassing a vast and varied body of work that spans both five decades of asylum history and myriad approaches to artistic practice.

Mr A Moves in Mysterious Ways: Selected Artists from the Adamson Collection, curated by Dr Heather Tilley and Dr Fiona Johnstone, features painting, drawing and sculpture selected from some 6000 art objects, all produced under the guidance of pioneering art therapist Edward Adamson (1911-1996) by residents at Netherne Hospital in Surrey, a long-stay mental asylum, between 1946 and 1981. As part of a launch event a panel discussion was held in Birkbeck Cinema, where therapists, curators and artists alike shared their insights into Adamson’s life and legacy.

David O’Flynn from the Adamson Collection Trust and Val Huet from the British Association of Art Therapists spoke respectively about the development of Adamson’s work and ethos; the process of securing and displaying the collection – a task fraught with challenges, curatorial and conceptual – and about Adamson’s continued relevance to art therapy today.

Adamson defined himself not as a therapist, but as an artist; despite being instrumental in the foundation of the British Association of Art Therapists, he did not align himself with any one theoretical position. Adamson was an independent thinker who maintained his identity as an outsider as an act of affinity for those whose work he inspired and preserved.

Initially engaged at Netherne as a researcher into the relationship between mental illness and creativity, Adamson’s job was to encourage patients to produce work for clinical analysis. However, after the study ended in 1951, he established a studio where residents at Netherne were allowed to paint freely. He came to believe that making art was therapy enough; that creative expression could provide people with a bridge back to themselves. Working in this way Adamson amassed a staggering amount of material, writing the artist’s name and date of completion on the back of each piece, and so preserving not only the art object but the personal narratives of individuals otherwise anonymised by institutionalisation.

In exhibiting the work he collected, Adamson believed he could reengage the artists with a society that excluded them, and challenge pre-conceived ideas about the capacity of the mentally ill to contribute meaningfully to culture. As Val Huet emphasised in her talk, Adamson’s lasting impact upon contemporary art therapy was in situating “art at the heart” of therapy; extending artistic agency beyond the borders of allotted therapy time. As continued cutbacks to mental health budgets put pressure upon this practice-based approach, a reassessment of Adamson’s pioneering work becomes more topical, timely and, potentially, radical.

Beth Elliott, a trustee of Bethlem Gallery, and their artist-in-residence Matthew, spoke about the development of artistic practice inside the institution, and the unique pressures, restrictions, and surprising affordances of the clinical environment. Matthew’s description of his own process, together with the slides of his vibrant and luminous artwork, was a clear argument for the persistence of practice at the centre of therapy, demonstrating how art within the asylum can be an imaginative escape, a tool for navigation, and a strategy for resistance.

Invigorated by the talks, people headed towards the Peltz Gallery where the work of eight artists is on display, including pieces by Martin Birch from whose arch drawing of Adamson the exhibition takes its title, and Gwyneth Rowlands, whose eerie and arresting painted flints were my personal highlight of the exhibition.

It is worth noting that this is the first time the artists have been named in an exhibition; their work attributed to an individual with a unique aesthetic outlook and approach, not shown as an undifferentiated mass of “asylum art”. From Mary Bishop’s bold blocks of Constructivist colour to Rolanda Polonsky’s intricate, spooling pencil drawings, the work defends its right to be considered first and foremost as art. This exhibition asks us to consider the meaning of the phrase “outsider artist” and where in that description the emphasis should be placed.

Mr A Moves in Mysterious Ways interweaves a diverse array of narratives – personal and medical. It is an insight into changing psychiatric practice, a celebration of Adamson’s work, and also a testament to eight unique artistic visions and histories.

Fran Lock is a poet and practice-based PhD student in her first year at Birkbeck

On Thursday 18 May I introduced an event about the politics of US fiction since the 1960s. This was part of Arts Week 2017, and a contribution to the theme of art and politics which was one element of this year’s series of events. Though I had been involved in organizing the event, its substance was provided by two speakers,

On Thursday 18 May I introduced an event about the politics of US fiction since the 1960s. This was part of Arts Week 2017, and a contribution to the theme of art and politics which was one element of this year’s series of events. Though I had been involved in organizing the event, its substance was provided by two speakers,