Charlotte Deadman, a postgraduate research student at Swansea University shares insights from the Arts Week workshop led by Birkbeck’s Tobias Harris and Joseph Brooker who delved into the famous column by Myles na gCopaleen.

It was a capacity audience for the Irish Times: Myles na gCopaleen’s Cruiskeen Lawn workshop presented by Birkbeck’s Tobias Harris and Joseph Brooker as part of this year’s Arts Week.

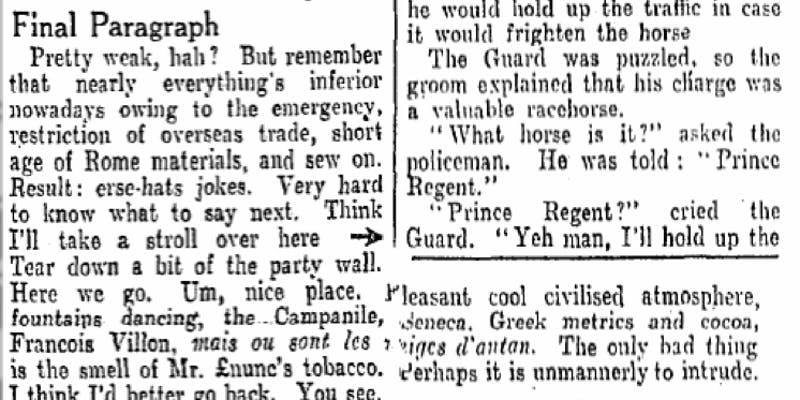

The workshop’s theme was a discussion of the four million words – equivalent, we were told, to 16 Ulysses. The famous column was penned by the Irish writer Brian O’Nolan using one of his many nom de plumes (here Myles na Gopaleen, an amusing intertextual reference worth Googling). The column appeared in the Irish Times from 1940 until the writer’s death on April Fool’s Day, 1966 under the heading Cruiskeen Lawn (another amusing intertextual reference…).

Operating as a kind of ventriloquism, the column’s purpose was to call out literary poseurs and their ilk – ‘corduroys’ as Myles nicknamed them and anybody else who got his gander up – by a mix of satire, cliche and faked texts and general ‘outpourings of derision’ upon his chosen victim/s. It was explained that the column started as a result of O’Nolan deluging the newspaper with letters attacking other letters within the paper – letters that very often had been manufactured by O’Nolan or Myles and/or his chums from his old days at University College Dublin. While this special breed of entertainment was eagerly savoured by the paper’s readership, it became a matter of increasing concern to its then editor, Bertie Smyllie, who by degrees became uncomfortable with content and tone of the letters in light of the censorship laws then energetically operating within the Irish Free State. As a result, Smyllie decided that the best course of action was to harness and tame the animal; he did this by inviting O’Nolan to become a regular contributor: the Cruiskeen Lawn column was the result.

Appearing initially in Irish (O’Nolan was a gifted linguist able to write fluently in several languages – Irish, English Latin and German); an early major target for the column was the Irish language revival movement – Douglas Hyde being a favourite target. By 1942 the column appeared half in Irish and half in English, reflecting O’Nolan’s increasing gloom regarding the future of the Irish language. The column was eventually published entirely in English, we were told much to Bertie Smyllie’s disappointment as he was keen to keep the Irish Free State on side. The Irish Free State was a predominantly Catholic body with a passion for promoting the Irish language at an immense financial cost, regarding it as representing the core of a true Irish identity.

The workshop romped through a dizzying selection of readings to be found in a compendium – The Best of Myles – which were complimented by readings performed by the wonderful Hugh Wilde with brilliantly entertaining gusto. As would seem inevitable, Brian O’Nolan as Myles na gCopaleen ultimately went too far: working as a civil servant in his day job, O’Nolan had for years relentlessly mocked his bosses, who knew full well the true identity of the troublesome columnist – and fired him. This was a fabulous evening. My thanks to Arts Week.